In 1928, Alraune – a groundbreaking, unique science fiction movie – made waves in silent-era Hollywood. Now, over one hundred years later, it is all but forgotten. Sara Century revisits an unsung masterpiece to bring you the story of the movie, and what makes it so great.

The story of Alraune is loosely based on the folktale that the hallucinogenic Mandrake Plant is created when the ejaculation of a hanged man hits the earth. I know science when I hear it, and that’s just plain science, folks. The Mandrake Root is vaguely human shaped, so it was widely believed to have all kinds of mystical abilities. In 1911, Alraune first appeared as a sexually charged horror novel by Hanns Ewers. Though controversial, there were several subsequent film adaptations. Alraune the movie was made twice in 1918, one version of which is lost and the other which survives but is not easily accessible. The story was also made in 1928 as a silent film – and then remade in 1930 with sound but with none of the original cast except star Brigitte Helm. There is another remake in 1952 that also goes by the name Unnatural and keeps only the core concept of a wicked woman with strange origins seducing men.

The first two takes on the film are difficult to find much information on, but the 1928 version was written and directed by Henrik Galeen, one of the most important directors of German expressionist cinema. Galeen had written Nosferatu, worked on two silent versions of The Golem, and directed the unforgettable The Student of Prague, the 1926 take on the Edgar Allan Poe’s William Wilson. His works are marked by their surrealist atmosphere, and Alraune is no different.

In the 1928 film version of Alraune, a wealthy geneticist (a eugenicist, in this case) decides to perform an experiment in which he impregnates a woman that he considers to be “the scum of the earth” with a Mandrake Root. It is vaguely implied that he actually impregnated her a different way, but for the text of the script, it was the root. The amoral professor sends the child to a convent, where she refuses to conform to social norms and openly flirts with a number of men. Though her promiscuity seems to work out very well for her, the professor reprimands her and orders her to return home. While he places himself in a fatherly role, he lusts after Alraune. Eventually, she tells him that she knows of her origins, and he delightedly decides that she will either stay with him or he will simply kill her.

Alraune is one of the more emotionally complicated and even occasionally feminist silent films.

The way the professor dehumanizes Alraune and blames her for his own fixations is a fairly clear cut example of a man trying to control a woman that he has absolutely no respect for so, by the end, you’re likely to have a fairly positive view of Alraune despite her status as the “wicked woman.” The fact that the story so strongly sides with her is one of the most interesting things about it. During the time, it would have been very easy to simply villainize her and portray the professor as the one wronged, which many other films featuring unrepentant femme fatales did, and continue to do. Alraune’s embrace of her own amorality and her lack of interest in pleasing men that strive to exert control over her is honestly admirable, making this one of the more emotionally complicated and even occasionally feminist silent films, despite it utilizing a highly unlikely foundation for delivering that message.

Director Galeen helped bring to life some of the most sympathetic monsters of the silent era, and Alraune fits in as one of those hopeless outsiders like Nosferatu or the Golem. Helm does an incredible job of portraying her, and the unrepentant power that emanates from her is enough to give chills even nearly a century later.

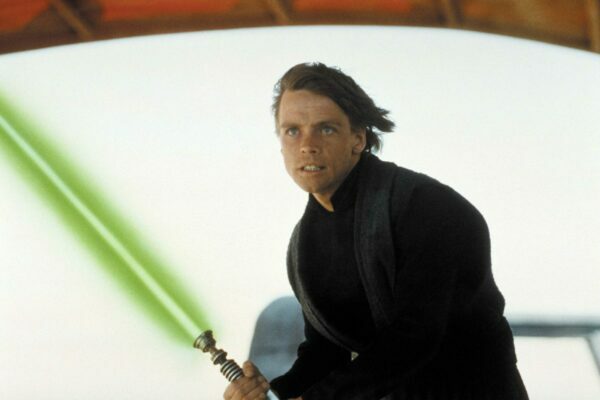

The 1928 version of Alraune in all its glory.

One important thing to note about this bizarre story is how the people behind it were affected by the rise of the Nazi party in Germany. To begin with, the writer of the novel on which it is based, Hanns Ewers, quite literally was a Nazi for a brief time. Ultimately, his support of Jewish people and his possible homosexuality appears to have led him to fall out of favor with the Reich right as it fully claimed power in the early-30s. Ewers books were banned for years under Hitler, and he is now mostly forgotten despite his ahead-of-his-time instincts for sexual horror. Still, despite his enthusiastic nationalism, the sheer perversity of Alraune made it a highly controversial book. Alraune is the second in a trilogy, but sparsity of Ewers’ works in translation make it difficult to track down a functional copy. At the time, Eugenics was a hot topic of discussion, and indeed the tale does boil down to an attempt to genetically engineer a person. In this case, that meant creating a sort of anti-woman – not caring, not nurturing, not sympathetic – all cultural taboos for women in the moment and even now). The fact that the man behind the story did so for nothing more than his own pleasure is the real focus of the 1928 adaptation, not Alraune’s “immorality.”

Meanwhile, the lost 1918 take on the story was one of the early ventures of legendary Hollywood director Michael Curtiz. Though Curtiz left Hungary to work in the U.S., his sister, her husband, and their three children were all eventually sent to Auschwitz, only two of them escaping alive when the camp was closed. Director of the 1928 version Galeen was also Jewish, and his career in film ended in the fateful year of 1933, after which he went into exile before ultimately leaving Europe entirely. Brigitte Helm was not Jewish, but she was married to a Jewish man, and as a counterculture artist of late-1920s Berlin, many of her coworkers and friends would have been directly affected by Hitler’s very first attacks on marginalized populations. Hitler adored Helm, but Helm is said to have despised him, and rather than take part in Nazi propaganda, she left the film industry entirely and refused to speak on her career at all throughout the rest of her life. Anyone who watched Helm’s breakout role in Metropolis 1927) knows that this is an incredible loss to cinema.

As such, all the surviving versions of Alraune are not only bizarre takes on a truly bonkers story, but they are also historical artifacts that directly tie into one of the most infamous genocides in history, and they desperately deserve to be remastered. The existing cuts online are dark, blurry, and, at times, nearly unwatchable. This is too bad, because even if the sexual politics are dated, they have aged surprisingly well in many ways. Alraune is not a villain in her own story, and though marriage and a return to virtue save her in the end, the choice is in her power and she owns it. Until the 1952 version, which strongly deemphasized her autonomy, most renditions granted an ultimate power to the character of Alraune in some fairly surprising, even proto-feminist ways. If you choose to watch any version of the film, the 1928 one is going to be the way to go, but this remains a fascinating forgotten franchise in all its many forms.