Gladiator is over 20 years old. In celebration of the anniversary of a modern classic, Luke Walpole looks at the film’s legacy and its impact on the sword-and-sandals genre it epitomises.

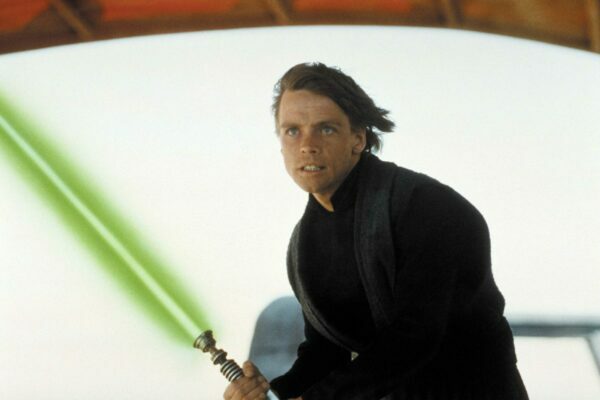

“Are you not entertained?” bellows Russell Crowe’s Maximus to a shocked crowd in Ridley Scott’s epic. For a while, we certainly were. Indeed, twenty-odd years ago, Scott’s take on sword-and-sandals was on its way to sweeping up pretty much every Best Picture award there was. Including, of course, an Oscar for both the film and its Antipodean star.

Few would argue that Scott’s film pulsed with an old-school Hollywood feel. The sets felt real, the action tangible and the canvas enormous. More so, audiences reacted well to the simplistic moral compass. Maximus was good and Commodus (played up by a gloriously menacing Joaquin Phoenix) was evil.

The searing ending to Gladiator

Here was the type of film which ‘Hollywood doesn’t make anymore.’ Gone are the days of The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964) and Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus (1960), two of many three-hour epics which focused on practical sets and an army of extras. But since Gladiator, Hollywood’s record at recreating sword-and-sandals has been patchy at best. Even for Scott, Kingdom of Heaven (2005), Robin Hood (2010) and Exodus: Gods and Kings (2014) saw diminishing returns both critically and financially.

The rot doesn’t stop there. Clash of the Titans, the 2010 remake of the 1981 film of the same name, sought to marry up the old-school feel of Ray Harryhausen’s work with a more modern, CGI edge. The response was tepid, and though it merited a sequel, Wrath of the Titans (2012) took $150 million less at the worldwide box office than its predecessor. Unsurprisingly, talk of a three-quel has been muted.

Tales of financial woe have been common throughout the last twenty years. 2016’s Ben-Hur remake lost $6m and King Arthur: Legend of the Sword (2017) lost $25m outright, while Pompeii (2014) and The Eagle (2011) undoubtedly lost money post-marketing costs. Perhaps this would feel more disappointing if the films were of a high quality. While there is definite fun to be had with Guy Ritchie’s cockney King Arthur, or even Alex Proyas’ completely dreadful Gods of Egypt (2016), the fact remains that the sword-and-sandals genre is dying a slow and painful death.

So, what’s changed? Two things, really. Mere months after Gladiator’s triumph at the Oscars, Peter Jackson changed the game. The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001) – to my mind the greatest blockbuster this century – completely remoulded what the genre could do. The mixture of tactile film-making with WETA studio’s pioneering CGI work made Middle-earth appear both tangible and ethereal. The film, and the series as a whole, heralded the end of sword-and-sandals as we know it.

Instead of dusty Roman roads there was the shining city of Minas Tirith. Why have sword-and-sandals when swords-and-sorcery could be created so convincingly? This tonal shift made fantasy accessible and, whisper it quietly, quite cool for a time. Since, both film and TV executives have been more willing to greenlight fantasy stories with a mass market appeal. Without Lord of the Rings, we probably wouldn’t have had Game of Thrones (and the numerous films and tv shows which have sought to emulate it), or more recently Netflix’s The Witcher. Jackson’s trilogy grossed just shy of $3bn at the Box Office, with Return of the King (2003) taking home eleven Oscars in the process. The fact that Amazon are investing a record amount of money into their own Middle-earth series underlines this confidence.

The ride of the Rohirrim in Return of the King

Audiences’ move away from sandals and towards sorcery was ably backed up by technological advances. Advances which also helped Sci-Fi filmmaking to grow exponentially. The explosion of superhero films could only have been achieved through improved CGI and VFX, and the genre has capitalised on this remarkably well.

The flip side of the coin is that technological advances have – in some instances – stripped sword-and-sandals films of the tangibility which always made them so enjoyable. Instead of visceral action they’re more often mired in shaky effects and CGI soup.

The result of this is that the rise of fantasy and continual technological improvements have seen sword-and-sandals increasingly crowded out of a saturated blockbuster market. Even when they do get made, the success of Gladiator still looms large. Unable to capture audiences’ imagination in quite the same way as in the past, the genre feels dated. Perhaps Maximus’ tutor Proximo was right in his worldview. When it comes to sword-and-sandals, all that remains are shadows and dust.