For fans of action cinema, John Woo is a towering figure who has made some of the most entertaining films in the genre. Jim Malakwen dives into Woo’s filmography to examine his legacy and how big an impact he made on action movies since.

After spending years honing his craft in the Wuxia (Chinese Fiction concerning martial artists) genre, John Woo found mainstream success with 1986’s A Better Tomorrow. This piece will explore the work he made from that period onwards in an effort to discover just what exactly made his movies so unique and riveting.

A Stunning Style of Filmmaking

John Woo’s highly stylized directing has had a huge influence on today’s filmmakers. Some of Hollywood’s biggest names such as Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez have cited him as influences on their work. And rightly so, the man can make the most mundane act seem cool and gripping. A key element of his aesthetic is the use of slow motion – a technique he learned from watching the films of Sam Peckinpah, The Wild Bunch (1969) in particular.

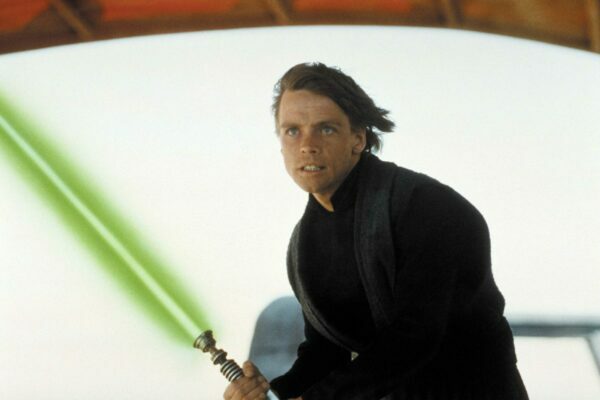

The famous shoot out scene that features in the climax to The Wild Bunch (1969).

Because Woo tends to cover an action scene with multiple cameras, all shooting at different frame rates, a shootout can have an almost operatic feel. Sparks fly, squibs go off on hapless goons as the hero leaps across the screen, twin Berettas blasting away.

Hard Target (1993), Woo’s first Hollywood film, paired him with one of the biggest action stars of the early nineties, Jean-Claude van Damme. Despite a tumultuous production, Woo was able to deliver an enjoyable experience that had everything action fans would want in that collaboration. The usual Woo trademarks of slow motion shootouts and chase scenes meshed harmoniously with van Damme’s martial arts prowess.

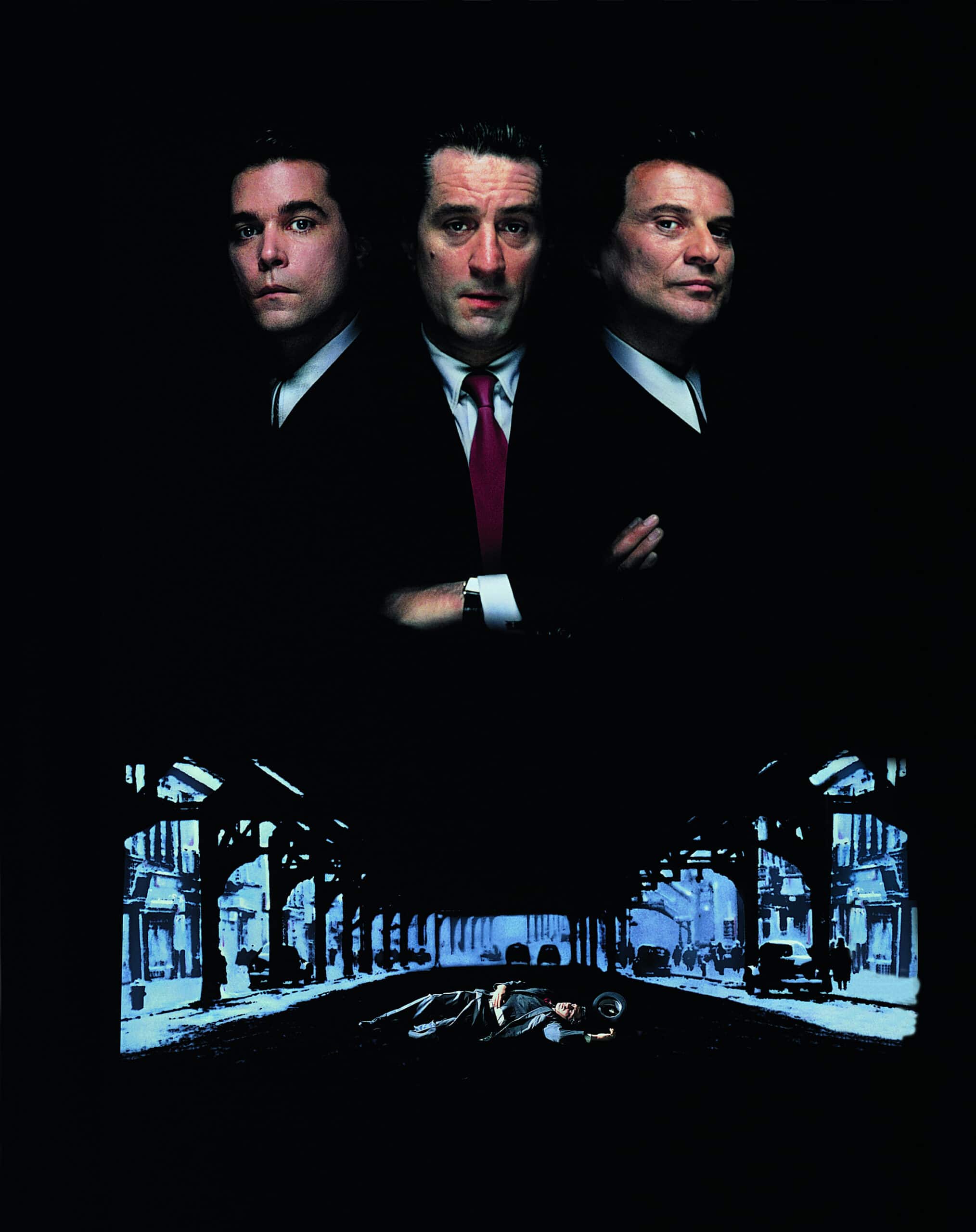

The bar shootout in Robert Rodriguez’s Desperado (1995) is an exceptionally well executed homage to Woo’s Hong Kong output and one of the best attempts by a Western director to mimic his style.

Ingenious Use of Locations for Stunts and Shootouts

The inventive use of locations to create memorable set pieces is an essential component that makes Woo’s action scenes so kinetic. The one-shot hospital shootout in Hard Boiled (1992) is a spectacular demonstration of his ability to create mayhem from the seemingly mundane. This iconic display of virtuoso filmmaking sees Chow Yun Fat’s inspector Tequila partner up with Tony Leung’s Alan as they infiltrate a hospital taken over by criminals. The usual Woo hallmarks are on display: a hero wielding twin automatic pistols, slow motion, as well as the use of a technique rarely seen in his movies – filming the majority of the set piece in one take. The use of an unbroken shot, a novelty in 90s action cinema, allowed the unseen set designers to alter the location to fit the requirements of the sequence while also enhancing the audience’s enjoyment of the action.

The astonosihing one-shot action sequence in Hard Boiled (1992).

The church gunfight at the climax of The Killer (1989) is another illustration of how locations can be used to create thematic resonance. The film’s protagonist, played by frequent collaborator Chow Yun Fat, is an assassin attempting to atone for a horrible mistake he made at the beginning of the movie. This spectacular set piece sees him unite with a policeman to ward off waves of gangsters out to murder them. This sequence would also mark the first use of doves in a John Woo film – an extension of the director’s affinity for religious imagery.

Today, competent action directors realize the importance of locations in fight scenes. Prachya Pinkaew’s Protector (released in the UK as Warrior King in 2005) has a memorable set piece that’s a perfect example of how a one take action scene can showcase both a lead character’s martial arts prowess and the imposing location he must traverse in order to confront the bad guys.

Masterful Pacing That Sets-up The Action

Pacing is another crucial part of a John Woo film. His movies often begin with a bang like in Hard Target and The Killer before proceeding to introduce the protagonist, the villain and the dramatic question. Woo, ever the gifted showman, knows the importance of familiarizing the audience with the world of the story before proceeding to the pyrotechnics his fans crave. At some point in his films, the action sequences become more inventive and demonstrate his remarkable ability to choreograph dance-like shootouts that culminate in a Mexican standoff and the appearance of doves. The recurrence of these motifs in his work mark them as a signature element in his oeuvre.

The tea house gun battle in Hard Boiled is a master class in terms of pacing. By meticulously taking time to introduce Inspector Tequila, the gun smugglers and the reveal of automatic weapons, the sudden explosion of violence becomes much more impactful.

The Matrix (1999) was directed by the Wachowskis and is one of the most influential action films of the last couple of decades. The movie’s dynamic action scenes were heavily influenced by John Woo’s aesthetic. The Wachowskis knew the importance of pacing, and thus saved their most impressive gunfight for the sequence where Neo and Trinity rescue Morpheus. The lobby shootout has loads of Woo imagery: sun glasses, trench coats, dual-wielded handguns and slow motion gunfights.

Movie Violence versus Real Violence

Finally, in a discussion about John Woo, it would be important to address the issue of violence. Arguments have been made that his films glorify violence with over the top gunplay. At the height of his popularity, Woo’s movies were often thought of as incendiary material that could potentially influence unstable individuals to carry out unspeakable acts. While opinions on this issue are varied, it’s best to remember that these movies were made for mature audiences who are aware that what they’re watching is simply an experience made for their enjoyment. And enjoyable experiences they certainly are. Violence is inherently cinematic. Just look at the recent success of the John Wick (2014-present) films. The filmmakers behind the series (Chad Stahelski and David Leitch) have a background in stunt work and use their expertise to create exhilarating action sequences, in a similar vein to John Woo. The big screen allows moviegoers to enjoy a vicarious thrill without actually taking part in what they’re watching.

The Killer Remake

John Woo is currently working on a remake of The Killer with a female lead. Expectations are high that this will be a return to form for one of action cinema’s most dynamic talents.

The action genre is in an exciting place at the moment. After years of enduring badly staged, overedited, shaky cam fight scenes, movie fans seem to be responding positively to the creativity employed by today’s directors. Filmmakers like Chad Stahelski eschew a reliance on CGI in favor of practical stunt work and special effects. Like all good artists, they’ve studied the work of pioneers like John Woo, a man who’s certainly earned his place in the Pantheon of action cinema.