Waterworld is one of the most famous box office flops ever made. Is its reputation justified, though? Bianca Garner dives in the deep end to bring us the stories behind a famously troubled production.

Waterworld is a film whose famously troubled production history is more talked about the content of the film, regarded as one of the biggest box office flops of all time. Since its release 25 years ago, there have been numerous stories about how the film’s budget spiralled out of control, with costs coming in at $175 million (a big budget now that was unthinkable back in 1995), disasters involving sets being destroyed by bad weather, and tensions running high between the director, Kevin Reynolds, and its leading man, Kevin Costner. However, was Waterworld really the disaster that we have been led to believe or is the truth a little more complicated?

The idea for Waterworld emerged during a conversation between screenwriter Peter Rader and producer and co-founder of the Motion Picture Corporation of America (MPCA), Brad Krevoy. Rader pitched his idea of a “Mad Max-style post-apocalyptic film” back in 1986, but Mad Max wasn’t his only source of inspiration. What Rader wanted to create was something that had “”a biblically epic scale” in nature, and drew on ancient Greek mythology, such as the legends of Helen of Troy and the Trojan war. Rader’s original script was commissioned by Roger Corman, the legendary B-movie producer of classic cult and exploitation drive-in movies, but Corman passed on the script once it became appaent it would not be possible to produce Rader’s screenplay for under $3 million.

Corman ended up selling Rader’s script, and it found its way to producers Andy Licht and Jeff Mueller, (best known for the low-budget teen comedy, License To Drive, 1988). They liked the Mad Max vibes but thought the film might be too close to Sergio Leone-style Spaghetti Westerns, with the main character being a drifter with no given name. Licht and Mueller believed the film could be shot for about $30-35 million, but nothing was officially approved as of yet. Another producer in the form of Larry Gordon also became attached to the project. Gordon has recently formed his own company Largo Entertainment, and he’d had recent success with the Kevin Costner film, Field Of Dreams (1989).

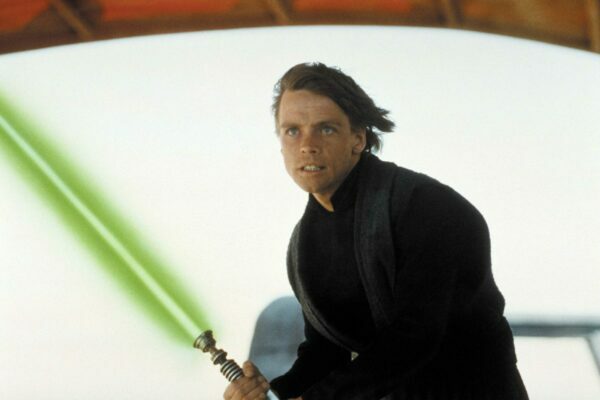

The theatrical trailer for Waterworld.

Waterworld’s original director was set to be Nils Gaup, best known at the time for his Oscar nominated film, Pathfinder (1987). However, by 1992, Waterworld had grabbed Costner and Reynolds’ attention, as well as that of the studio, Universal Pictures, and a budget of $100 million was approved for the film. With the big Hollywood names now attached, Licht and Mueller were forced to abandon ship. Radar was also asked to leave the project because he was considered too burned out by the rewriting process, and his script went through numerous rewrites, with screenwriter David Twohy (best known for The Fugitive, 1992, and writing and directing the Riddick trilogy), being brought on-board to develop the story further. In an interview, Rader described how he felt, “bummed out and disappointed,” that he had to leave, but in his own words, “that’s just the nature of the beast.”

Having both Costner and Reynolds involved should have made things a lot easier. In fact, Waterworld marked their fourth collaboration together, after Fandango (1985), Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991), and Rapa Nui (1994), the latter of which Costner co-produced but did not star in. However, throughout production, the two Kevins repeatedly clashed with each other, with Costner fighting to have more creative input with the story and his character’s arc, leading to Reynolds declaring that Costner was, “a backseat director”. And, to make matters worse, the film’s production costs were beginning to escalate.

By the time it came to start shooting in summer 1994, the budget had already ballooned to $135 million, with Costner’s own wage package being a cool $14 million alone. Even though shooting had begun off the coast of Hawaii, the script was still being rewritten as nobody could agree on an ending, with one of the script doctors being Joss Whedon (creator of hit TV show Buffy the Vampire Slayer).Whedon said he was essentially tasked with putting Costner’s own ideas into the screenplay, and described his experience as, “seven weeks in hell,” with neither Costner nor Reynolds taking his suggestions on board.

The budget spiralled out of control, with costs coming in at $175 million, disasters involving sets being destroyed by bad weather, and tensions running high between the director and the film’s leading man.

It wasn’t just script issues that Costner and Reynolds were facing, there were plenty of catastrophes involving dangerous stunts and natural disasters as well. A hurricane struck the floating Atoll set, causing it to sink, leading to the entire set having to be rebuilt. The huge-scale stunt-based ste pieces proved to be more probelmatic than anything else, with co-stars Jeanne Tripplehorn and Tina Majorino being thrown from The Mariner’s boat when the bowsprit snapped off, and needing to be rescued by a team of 12 divers.

Norman Howell, the stunt coordinator for the underwater scenes, came up too quickly from a dive and suffered an almost fatal case of the bends. One day on the shoot, Costner’s own stunt double, Laird Hamilton, was riding his jet ski across 40 miles of open ocean to get to set and, after his jet ski ran out of gas, he was swept ot to sea by a freak storm. It took a rescue helicopter most of the day to find him.

Costner himself nearly died during a sequence when he was lashed to the mast of his boat. The craft ended up drifting off to sea, and it took another rescue team to reach the star and untie him. (Costner may have been problematic for Reynolds, but there’s no denying the level of dedication that the actor had for Waterworld. He was on the set for 157 days, working 6 days a week).

The stress of these disastrous stunts and accidents, as well as Costner’s constant meddling, led to Reynolds leaving the film during post-production, less than three months before the film’s release. With Reynolds out of the picture, Costner now had full creative control. His very first act as director was to fire composer Mark Isham (known for working on dramas such as Little Man Tate, 1991, and Of Mice and Men, 1992) because his score was considered, “too ethnic and bleak,” for Costner’s vision. At the last minute, James Newton Howard (The Fugitive and Wyatt Earp, 1994) was hired instead.

Throughout the entire course of the production, rumours had been circulating about the budget spiralling out of control and the onset disasters, leading to some critics to dub the film the”Fishtar” and “Kevin’s Gate”, in reference to legendary mega-flops Ishtar (1987) and Heaven’s Gate (1980). Contrary to its reputation, Waterworld actually had a reasonable theatrical run and, on 28th July 1995, it opened at No.1 at the box office. It managed to make back $88 million in North America and another $176 million overseas. Despite all this, Waterworld was declared a box office flop because the production costs ended up at an astronomical $175m.

Reviews were mixed, with Roger Ebert describing the film as, “one of those marginal pictures you’re not unhappy to have seen, but can’t quite recommend”, and the film ended up being nominated for 3 Razzies (Worst Picture, Worst Director for Reynolds, andWorst Actor for Costner) and winning 1 (Worst Supporting Actor for Dennis Hopper). Still, Kevin Costner has said that he’s very fond of the movie: “It stands up as a really exotic, cool movie. I mean, it was flawed — for sure. But, overall, it’s a very inventive, cool movie. It’s pretty robust.” And, in hindsight, he might make a valid point. Waterworld is a flawed film, but it is also quite an inventive one too, in regards to its huge-scale water-based set pieces, and inarguably impressive production design. It wasn’t the classic Universal may have hoped for but, with the amount of drama and history on and off screen, it’s certainly one of the most interesting production stories in Hollywood.