Disney are currently excising global domination at the box-office, and their slew of live action remakes of their own properties are providing a big slice of the action. Isabelle Bousquette examines the Disney strategy, and whether there may be a bigger motive here beyond the bottom line.

When Disney’s new streaming service launched in November 2019, Bob Iger had promised that it would include, “the entire Disney motion picture library.” However, one feature film was notably absent: Song of the South (1946), an unabashedly racist portrayal of southern plantation living that Iger himself called, “fairly offensive.”

Some agreed that the film should remain hidden. Others believed the film could be used as a teachable moment and a reflection on the unjust attitudes of the past.

Regardless of whether Song of the South was rightfully excised, this incident highlighted the central paradox of the Disney brand: the tension between nostalgia and a forward-looking, inclusive liberalism.

The constant rehashing of the iconic films is more than just guaranteed box office profits, it’s a way for the studio to rewrite its complicated and problematic history.

The Disney magic relies on the Disney legacy. It looks back on a canon of 200 beloved children’s films. The problem arises when that canon and that legacy is in conflict with the inclusive 2020 vision for the Disney brand.

Throwing out Song of the South was one thing, but the truth is that almost every pre-millennium Disney film has some non-PC element. How do you rewrite that uncomfortable history? For Disney, the answer is simple: you literally rewrite it.

When Disney first started releasing live action remakes of their animated classics, it felt financially motivated. They knew they could create a surefire box office success because they were making a movie that the audience already knew and loved. However, perhaps that wasn’t the only reason. Maybe these remakes were a way for Disney to rewrite its own history, and put itself indisputably onto the right side.

That’s what they accomplished with Aladdin, a 1992 Disney classic that didn’t necessarily age well into the 21st century. The setting, Agrabah, felt like an amalgamation of stereotypes from every Middle Eastern and North African country. Several lyrics from the film’s opening song, Arabian Nights, were widely criticized for being racist after the 1992 release. The controversy mainly surrounded the lyric: “Where they cut off your ear if they don’t like your face, it’s barbaric, but hey, it’s home.”

Later in the film, another song references the Muslim holy day as “Sunday salaam,” despite the fact that the actual holy day is Friday. The 2019 remake gave Disney the chance to fix these problematic hiccups. The Arabian Nights lyric was changed to, “Where you wander among every culture and tongue, it’s chaotic, but hey, it’s home.” And, “Sunday salaam” was changed to “Friday Salaam.”

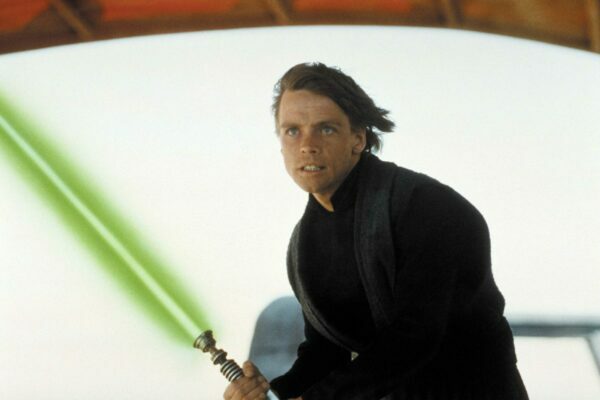

Will Smith as the Genie in his big musical number in the live action version of Aladdin.

However, the most striking difference between 1992’s Aladdin and the 2019 reboot seems to be the way the different movies treat women. The original Aladdin, despite being a children’s movie, portrayed women that were, in a word, sexualized.

During the Genie’s opening number, scantily-clad belly dancers wave their cleavage in Aladdin’s face. Jasmine herself doesn’t wear much clothing. Then, in the film’s climax, she distracts Jafar by trying to seduce him. None of these elements were recreated in the 2019 version. The Genie’s backup dancers are made up of male genies. Jasmine is noticeably more covered up. And, instead of using her sexuality to manipulate men, she demands political power in her own ballad, Speechless, a song that didn’t appear in the original.

The new Aladdin rails against the very type of sexism that seems rampant in the original. In this way, Disney overwrites its problematic original and leaves the audience with the image of an empowered woman fighting for her voice.

Disney’s Beauty and the Beast (2017) remake also represents a conscious shift in the way Disney wanted to present its legacy. The 1991 original was markedly less controversial than Aladdin, which meant that here, Disney wasn’t tasked with the job of ‘fixing’, as it was able to explore new possibilities that underscored the Disney brand identity.

In the original, LeFou was Gaston’s bumbling but forgettable sidekick. In the 2017 remake, he becomes Disney’s first openly gay character. His allegiance to Gaston is explained in the context of a romantic crush. At one point, Mrs. Potts tells him that he can do better than Gaston. Then, during the group dance finale, Lefou begins waltzing with another man, before they share a knowing look.

The truth is that LeFou isn’t as openl” gay as many characters you’ll see onscreen elsewhere. However, the change in LeFou’s sexual orientation in the remake certainly feels deliberate. Josh Gad, who played the character, said he was, “beyond proud” to participate in this landmark moment for Disney’s on-screen representation.

Instead of becoming just another fairytale romance, Disney’s version of Beauty and the Beast becomes a groundbreaking and inclusive portrayal of a minority group.

Even a film like 2019’s The Lion King, which nearly feels like a shot-for-shot remake of the animated 1994 version, made some important changes.

When the original The Lion King was released, it was met with widespread acclaim. However, viewers struggled with one thing: the scavenging hyena characters felt undeniably racist against African Americans. Whoopi Goldberg and Cheech Marin played the hyenas with accents evocative of lowlife gangsters. They spoke in slang and represented a population from the wrong side of the tracks. It’s possible they wouldn’t have been so problematic if more of the film’s central characters were also voiced by minorities. But instead, Simba and Nala were played by Matthew Broderick and Moira Kelly.

The opening sequence of 2019’s The Lion King live action remake.

That was one change that was easy to accomplish in the remake. Simba and Nala became Donald Glover and international superstar, Beyoncé. The hyenas themselves also changed, becoming more scary than comedic. In that way, they’re able to liberate themselves from being the butt of everyone’s joke – they’re no longer foolish and idiotic. They are bonafide villains. They are able to prove that when one of the hyenas battles Nala during a climactic moment that never appeared in the original.

The shot-for-shot nature of The Lion King remake gives you a sense that the 2019 version can really stand in for and replace the 1994 version. In this way, Disney can again write over the uncomfortable racist moments from the original with something a little more on brand.

Disney isn’t alone among long-standing film studios with a murky history of racism, sexism and other prejudices running through their canons. However, Disney’s place is unique in that its iconic stature rests largely (to an extent) on nostalgia. These are the movies you grew up watching. These are the movies your kids will grow up watching.

Disney is now in a position that it has to marry that nostalgia with a PC forward-looking attitude appropriate to 2020. It has done that by literally rewriting its own past, by rewriting the very films that define the Disney brand. And it’s not done. It has no fewer than twelve live action reboots currently in development and pre-production, including Peter Pan, Snow White and the Seven Dwarves and Bambi.

So when you look back on the Disney canon, you don’t see it with problematic side characters and warts and all. You just see the polished reedited inclusive version of it. It’s up to every viewer to decide whether or not that’s a good thing.